Sleep is really important! When we don’t get enough of it, we can find it hard to concentrate, we forget things, our reaction time is slower, our mood drops and our emotional resilience is decreased. In the longer term, poor sleep can impair our immune function making us more susceptible to colds and flu’s, and increasing our risk of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

Around 50% of young people report problems with sleep including difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep, poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness. Although pain and sleep are closely tied, it seems that sleep impacts pain more than pain impacts sleep. When we experience insufficient sleep on a regular basis, the biochemical and inflammatory responses in our bodies change, disrupting our natural pain management systems. What does that mean? Well, it means that our natural pain protection system becomes over-protective and our sensitivity to pain increases (4). So, optimising sleep is an important part of pain management!

What’s a “normal” sleep pattern?

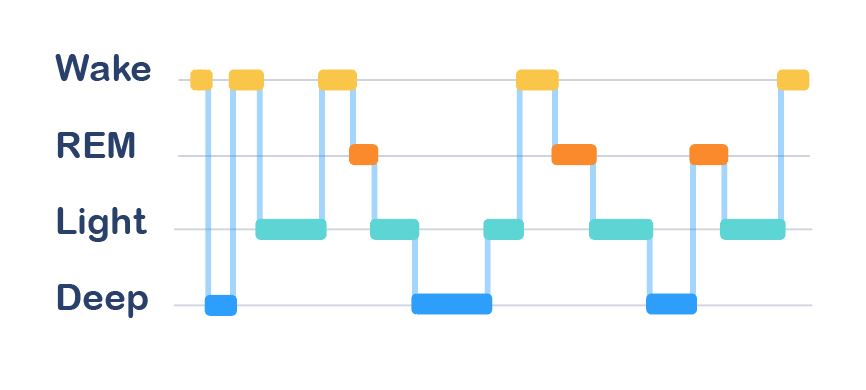

Sleep is often thought of as a single cycle where you fall asleep, move from light sleep to deep sleep, back to light sleep, and then you wake up. Turns out, that’s not how it works. As you can see from the graph below, we actually go through several of these cycles each night; each cycle lasting about 90 minutes. The other thing you’ll notice in the graph is that waking up across the night as we move through these cycles is completely normal – even if we don’t always remember it. Although about half the night is spent in light sleep, it’s the deep sleep that really recharges our batteries.

So, how do you know if you’re getting a good night’s sleep? (5):

- You get to sleep reasonably quickly when you go to bed (<30 minutes).

- You don’t wake up very often (<2 times per night) and when you do, you fall back to sleep reasonably easily (<30 minutes).

- You nap once a day at most, and when you do, you keep it short (<30mins).

- You wake feeling refreshed and you don’t feel overly tired during the day.

Does sleep change as I get older?

Sleep changes a lot from birth through to adulthood. As we age, our sleep becomes shorter, and lighter and we wake more often during the night.

Adolescence is a critical point for change, with the natural sleep-wake cycle of older adolescents drifting to a later time zone – meaning you might find you want to go to bed later at night and sleep longer in the morning. Although staying up later might seem fine, the sleeping-in part can be tricky when commitments like school, sport, and work require you to get up earlier than you would like to.

The Sleep Health Foundation recommends that adolescents get around 8-10 hours of sleep each night, while young adults need around 7-9 hours. In reality, many young people average much less than this, leaving them with a sleep deficit during the week that they then try to reduce by sleeping late on the weekend. Sound familiar?

Tips to help you improve your sleep

Many sleep difficulties can be improved by following the principles of “sleep hygiene”; a collection of behaviours and habits that promote good sleep. You can really improve your overall sleep pattern by paying attention to things like your sleep routine, environment, pre-bed behaviours and dietary intake.

Routine, routine, routine

When it comes to a good night’s sleep it’s all about the routine. Ideally, this means following a set bedtime and wake-up time every day. That can feel tricky when you create a sleep deficit during the week which leaves you wanting to sleep later on the weekends, but routine is really important for resetting your body clock.

Routine is also about what you do before bed. When you were little you might have had a pre-bed routine that included something like a bath, a bottle and a story – that routine helped cue your brain for sleep without you even realising it. While you might not need someone to read you a story before bed anymore, setting a clear routine that you follow each night will help get you ready for sleep before your body even hits the bed. It doesn’t have to be long – it just has to be consistent. Some people like to have some quiet time to wind down before bed; others prefer to keep it short and simple. A simple pre-bed routine might be something like having a glass of warm milk or doing a brief relaxation exercise, brushing your teeth, popping on your PJ’s and climbing into bed.

If you’re struggling with your sleep, then consider:

- Setting yourself a simple pre-bed routine to help cue your body for sleep. You might even like to use one of the many sleep or health apps that offer bedtime and pre-bed wind-down time reminders.

- Going to bed at the same time every day and getting up at the same time every day

Make a really strong link between bed and sleep

The pre-bed routine is about sending a message to your brain that says “I’m about to go to bed so get ready to sleep”. When we get into bed, we then need to back it up with a message that says “I’m in bed – it must be sleep time”.

The best way to reliably send that message is to make a really strong association between bed and sleep. Thinking about the younger child example again – little kids don’t do anything in bed other than sleep. They get up to do everything else. As we get older, some people start to do more things in bed like reading, playing on devices, watching TV, and maybe even eating. All these different activities in bed mean the association between bed and sleep is broken.

In short, if you want to cue your body for sleep then:

- Only use your bed for sleep (and sex or masturbation).

- If you can’t sleep after about 20 mins, get up and only go back to bed when you are feeling sleepy.

- If you need to lie down during the day then do it somewhere other than in your bed.

Make an environment that’s conducive to sleep

Like Goldilocks, we sleep best when our environment is “just right”. That means:

- A comfortable bed

- A dark and quiet room

- A temperature that’s not “too hot” and not “too cold” (around 18-24°C).

Relaxation

Your nervous system becomes sensitised when you experience chronic pain and this can make it harder to get to sleep. Relaxation is a great way to help combat it – it’s good for sleep and good for pain.

There are almost as many different relaxation exercises as there are episodes of The Simpsons and it really doesn’t matter which one you use. You might find a favourite that you always use, or you might develop a range of options that you can pick from depending on how you’re feeling at any given time.

- Relaxation before bed can help calm the system and improve sleep.

- If you’re struggling to sleep at night, relaxation exercises can be a great way to fill the time until you get sleepy. It can also help to quiet a racing mind and re-direct your attention away from unpleasant sensations or thoughts.

Bright light therapy

Our natural sleep-wake cycle, or body clock, is regulated by our circadian rhythm, which in turn, is driven by light. Exposure to bright light at specific times of the day can help regulate your body clock because it suppresses the production of melatonin within your body, increasing your level of alertness and making it harder to get to sleep.

If you are working with a sleep professional, bright light therapy uses artificial light that’s delivered through a device like a lightbox or glasses. You can also follow the principles of bright light therapy to improve your sleep using natural lights.

- If you want to get to sleep earlier than you currently do, avoid bright light in the early evening and night. This includes prolonged use of screens before bed. Instead, use dim, orange or warm-coloured room lights and dim, blue-filtered screens.

- If you struggle to wake up in the morning, seek out bright light first thing, perhaps by grabbing your breakfast outside in the sunlight, or sitting in front of an open window. It also helps to get plenty of light during the day by being out in the sunlight or using bright overhead lights.

Physical activity

Physical activity can reduce chronic pain as it helps stimulates blood flow to the muscles, quieten the nervous system and calm the mind. It also helps stimulate deep sleep. Getting started can be tough though, especially when you have been experiencing chronic pain for a long time. The key is to start gently and gradually increase over time.

The timing of activity is important from a sleep perspective because exercise increases your level of adrenaline and alertness.

- Exercise in the morning can help get you going for the day.

- Exercise just before bed is best avoided, especially if you are struggling to get to sleep.

Racing thoughts

Ever found yourself lying in bed, ready to sleep but your mind just won’t turn off? You might be replaying things that happened during the day, looking ahead to future events, or going over things that are worrying you or making you feel anxious. Makes it pretty hard to sleep – right? You often notice it at this time of day because all of your other activities have stopped and you’re now lying in a quiet, dark room with nothing to distract you from your thoughts. If you find yourself struggling to mentally switch off, then you might like to try some of the following:

- Schedule some thinking time an hour or two before bed so that you can work through the things that are bothering you and develop a plan for addressing them.

- Try some relaxation or mindfulness exercises before bed to help you wind down and get ready for sleep. Relaxation can also be helpful if you wake up during the night and find it hard to get back to sleep.

- Keep some paper and a pen beside the bed so that you can jot down thoughts that pop up during the night. You can then put them aside because you know that they will be there ready for you to pick up in the morning.

- Keep a regular journal to self-reflect at a time that is convenient.

- If you find yourself worrying about how long you’ve been awake, or what time you need to get up in the morning, hide your clock so you don’t have a visual reminder of the time.

Food glorious food

The foods we consume have a significant influence on our function and wellbeing. This includes our sleep. Smoking and excessive consumption of alcohol and foods that are high in refined sugar have all been linked with sleep difficulties. Although stimulants such as caffeine are a popular way to help tired teens ‘get through the day’, caffeine consumption has been shown to decrease sleep duration in adolescents.

On the flip side, foods like almonds, milk and turkey have been said to promote sleep because they contain melatonin or tryptophans (an amino acid that promotes the production of melatonin) but you need to consume a lot of them to have any direct impact sleep.

So, although drinking a glass of warm milk is often recommended as a strategy to induce sleep, a single glass doesn’t have enough of these chemicals to improve sleep on its own – its power comes from being included as part of a pre-bed routine that promotes relaxation and cues sleep.

If you’re struggling with sleep, consider the following:

- Avoid excessive consumption of alcohol (if over 18 years of age) and foods that are high in refined sugar

- Limit your consumption of stimulants (e.g., caffeine, energy drinks, nicotine) and consider avoiding them altogether in the late afternoon and evening.

- Eat a couple of hours before bed; don’t go to bed feeling really hungry or really full, as neither is helpful for good sleep.

A word on napping

The natural tendency to drift towards a later bedtime can be problematic for young people when commitments like school, sport and work still require them to get up early in the morning.

Given that, it’s probably not surprising that up to 40% of teenagers find themselves taking a weekday nap. Napping can be helpful. A “power nap” of 15-30 mins in the middle of the day can improve your level of alertness and your cognitive function. However, the longer you nap and the later you nap, the more likely it is that your night-time sleep will be affected.

- If you choose to nap, keep it short (10- 30 minutes at the most) and do it before 3pm.

A word on technology

How often do you hear someone telling you to turn off your devices? Turns out they’ve got a point when it comes to sleep.

Choosing to stay up and use devices rather than go to bed can clearly impact sleep – it’s referred to as the displacement hypothesis (i.e., sleep gets displaced, or pushed aside, in order to do other activities). This can be addressed by making a deliberate choice to turn off the device and prioritise sleep.

The light that’s emitted from devices can also impact our sleep. Limiting the use of bright screens to a maximum of 2hrs before bed does not appear to affect sleep, but using them for longer than that can make it harder to fall asleep. Similarly, if you wake during the night and are struggling to get back to sleep, turning on a bright screen isn’t likely to do you any favours.

Of course, the other issue with technology is noise. Constant pinging from messages and alerts across the night does little to help you sleep.

If you want to ensure that your valuable night’s sleep is not interrupted by your device(s) then:

- Keep pre-bed screen use short (<2 hours), use a dim screen and turn notifications off before the time you want to go to sleep.

- Avoid using screens during the night.

- Leave devices outside the bedroom overnight. If they must be in your room, put them on non-vibrating silent mode and make sure the screen is facing down.

A word on mood

Our experiences of pain, sleep and mood are closely connected. Day-to-day stressors have a greater tendency to become overwhelming when sleep is disrupted because sleep disruption impairs our capacity for emotional reasoning and resilience, which can in turn, exacerbate feelings of anxiety, depression and stress. The impact of living with chronic pain stretches our emotional resources, making it harder for individuals to be emotionally resilient and to sleep well. Low mood has also been shown to increase the experience of pain and disrupt sleep. So, finding ways to improve your mood is just as important as finding ways to improve your sleep as both will improve your pain management.

Some options to help manage mood include:

- Learn some anxiety management strategies.

- Follow the tips outlined here to help improve your sleep.

- Connect with social supports.

- Prioritise yourself – make time to do things that you enjoy and pamper yourself.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle.

- Keep a regular journal.

- Participate in a course, like those offered by ‘This Way Up’.

- Seek some professional help.

What about medications and sleep?

Medications that you take for pain may impact your sleep – some can make you feel drowsy, while others can make you feel more alert. Sometimes, the sleep impact can be improved by adjusting the timing of the medication (e.g., taking it earlier or later in the day). There are also medications that can be prescribed by your doctor to help improve sleep in the short term, but they are not long-term solutions.

If you are interested in finding out more about how your medications might be impacting your sleep, then please discuss this with your General Practitioner or Pain Specialist.

Professional help

Getting a good night’s sleep is really important. Many sleep disturbances can be managed by following the advice outlined here, but some require more detailed input.

If you have tried the strategies listed above and are still struggling with poor sleep, then it might be worth chatting to your Health Practitioner or Pain Specialist about a referral to a Psychologist, Sleep Specialist or Sleep Disorder Clinic.

Want more information?

Here are some helpful resources to help you increase your knowledge about pain and develop strategies to manage your pain. Alternatively, if you want to talk to someone, please seek further assistance.

Finding a health professional team who can support you in your care is important. If you need expert help, ask your health professionals for their help or their recommendations for clinicians working in pain care.

Contributors

This module has been co-created by A/Prof Anne Burke, Dr Kate Bartel and Ms Ellyn Bicknell. The information in this module is based on current best-evidence research and clinical practice.

Related management modules

References

- Sleep Health Foundation, Australasian Sleep Association. Addressing Inadequate Sleep in the Australian Community: A Vital National Health, Societal and Economic Issue. Australia 2019. Retrieved from sleep.org.au

- Christensen J, Noel M, Mychasiuk R. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying the sleep-pain relationship in adolescence: A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019;29. PMID: 30621863

- Mellor D, Hallford DJ, Tan J, Waterhouse M. Sleep-competing behaviours among Australian school-attending youth: Associations with sleep, mental health and daytime functioning. International Journal of Pychology. 2018;55:13-21. PMID: 30525182

- Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, Kaur S, Mullington J. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020. PMID: 31207606

- Ohayon M, Wickwire EM, Hirshkowitz M, Albert SM, Avidan A, Daly FJ, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: first report. Sleep Health. 2017;3(1):6-19. PMID: 28346153

- Bartel KA, Gradisar M, Williamson P. Protective and risk factors for adolescent sleep: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2015;21:72-85. PMID: 25444442

- Kwon M, Park E, Dickerson SS. Adolescent substance use and its association to sleep disturbances: A systematic review. Sleep Health. 2019;5(4):382-94. PMID: 31303473

- Min C, Kim H, Park I, Park b, Kim, J, Sim S, et al. The association between sleep duration, sleep quality, and food consumption in adolescents: A cross-sectional study using the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e022848. PMID: 30042149

- Peuhkuri K, Sihvola N, Korpela R. Diet promotes sleep duration and quality. Nutrition Research. 2012; 32(5):309-319. PMID: 22652369

- Faraut B, Andrillon T, Vecchierini M-F, Leger D. Napping: A public health issue. From epidemiological to laboratory studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2017;35:85-100. PMID: 27751677

- Van den Bulck J. Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children. Sleep. 2004;27(1):101-4. PMID: 14998244

- Bartel K, Gradisar M. New directions in the link between technology use and sleep in young people. In: Nevšímalová S, Bruni O, editors. Sleep Disorders in Children. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 69-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28640-2_4